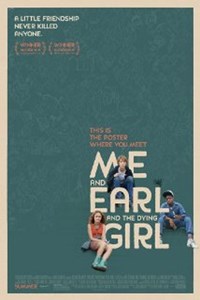

Starring: Thomas Mann, Olivia Cooke and Ronald Cyler II

Directed By: Alfonso Gomez-Rejon

Rated: PG-13

Running Time: 105 minutes

Fox Searchlight Pictures

Our Score: 4.5 out of 5 stars

Depending on how well you pitch it, self-loathing can be quite comical. Pointing out your own faults to elicit a laugh can work out well. I do it all the time with people I know because it allows me to show to them that I’m human, that I understand my flaws, and that I’m comfortable with my shortcomings…kind of. Then of course, across the way, there’s that thin line of self-loathing. It’s not too far and if you cross it, you find yourself in actual self-loathing territory. It’s a self-loathing that spins off into depression and depressing other people. “Me and Earl and the Dying Girl” beautifully blends a coming-of-age story and the tricky subject of youthful enmity.

When we first meet Greg (Mann), he’s socially awkward, but has mastered the art of fading into the background. Despite this, he’s maintaining a stable acquaintanceship with everyone in his school. He divides the cliques like world leaders divide their countries. He has it in good with the people of each land, but he maintains his own invisible island that has a unique identity, but he conceals it. The only person, who knows his interests, likes and dislikes, is Earl (Cyler). Like a lot of best friend stories, their meeting as elementary school students isn’t spectacular, but being young and impressionable does help build a firm basis friendship.

That young susceptible brain of theirs falls prey to Greg’s father, played by Nick Offerman, who is perpetually stuck as the bizarre and sage father in indie movies. Through his father’s influence, the two find a love for trashy, poorly made movies. Through that mutual admiration, they create their own parody movies of well-known movies like “Apocalypse Now” and “A Clockwork Orange”. This is Greg’s basic existence. It doesn’t seem like he wants to be bothered to do more nor does he want to attempt to do more, but that’ll quickly change.

At the request of his parents, he visits a former childhood friend, Rachel (Cooke). Everyone views the hangout time as beneficial for Rachel because she needs someone in her time of need. Technically, like everyone, she does. But Rachel is also someone that seems to be confident in her own minimalistic self-preservation. She doesn’t want to burden other people with her upsetting diagnosis, much less tell that to Greg, whom she barely talks to. Despite his awkwardness and many in-poor taste jokes, she finds his goofiness charming and sees the kindness in his soul.

Throughout, we’re reminded that this isn’t a movie where the two inevitably fall in love and have a cliché passion scene. That, in itself, is absolutely refreshing. It would cheapen what’s happening if she were to fall in love with the first boy to acknowledge her illness and be there in her time of need. It would feel cheap if he made a move as she goes through chemotherapy. They both care about each other, but not like that. They don’t need to. The love they feel for each other is completely platonic, but still very heartfelt.

At an integral point in “Me and Earl and the Dying Girl”, the movie turns on a dime from a comedy into a drama. It’s a very smooth, but sudden transition. Up until that point, Greg has been adorkable, but at that point, his darkness is revealed. Despite the minutes, hours, and days of concern he’s shown, this selfishness blooms and takes over. The situation and the muddying of his perception and the audience’s perception are done elegantly.

Coming-of-age stories have the inevitable growth, or at the very least a melancholy ambiguity haze hanging over them, at the end, and “Me and Earl and the Dying Girl” isn’t any different. It’s the filming and editing style, as well as the realism in our characters that helps propel this one into the top tier of this genre. It’s also great to see to see leads that aren’t impervious to emotional flaws and growing pains.